The only survivor of a shipwreck on the cliffs of the North Sea according to legend,

Heuling Friedrich Ashorn (112), the first of a stout German lineage, was

actually born in Scotland in the latter part of the 18th century. The teenaged boy was rescued by a

German fisherman and taken to Germany. Why he gave up his Scots name and didn't return to his

home is a mystery. Drifting to Brockhausen, Hanover Province, after he

was grown, Heuling

married Maria Elisa Luecken (113) and had three children, two girls and a

boy. Their mother died while giving birth to the youngest, Christoph Heinrich Ashorn, on

September 14, 1824.

Christoph Heinrich Ashorn (56) was raised by his oldest sister and friends

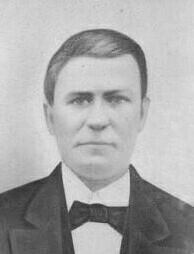

of the family. In 1854, Christoph married Carolina Liebscher (57) of Star Hill. Edward Ashorn (28), (pronounced Ed'-vard in German) was short and

stocky, maybe five-ten and 170 pounds. He had twelve children, but they never all lived at home

at one time. All their children survived many years, which was unusual in those days. Baptized

Friederich Edward Ashorn in 1857, he had ten siblings, eight of whom lived to raise families of

their own. Edward raised corn, cotton, sugar cane and sorghum near New Ulm, "like everybody else,"

says Della Kriegel. Even after he stopped actively farming they still grew some corn and maize to

feed the chickens. A garden grew behind the smokehouse, where Edward raised his own tobacco

to smoke in his corncob pipe. He cured the tobacco leaves in the smokehouse. They had a pretty

large persimmon tree, with big flat fruits, behind their house. There were also pear trees and a

row of three big pecan trees by the barn. At least one grew long Mahan-type pecans, while others

grew shorter Success-type pecans. You would go through the pecan trees to one of the two barns,

separate for cattle and horses. Edward only had two horses once he stopped farming. He would

use two for mowing and one for plowing the garden. One barn had a catwalk that you could walk

along as you put food in the stalls. Hog killing time came in winter. Instead of sausage casings,

Edward filled the bags in which he had bought tobacco, and tightened the drawstrings. The big

sausage balls became very dark but had no tobacco flavor.

Edward wasn't particularly affectionate, thought his wife Rosalia was. His grandson Riley

remembers that once Edward had a bad nosebleed and put a dime on his forehead to get it to

stop. He worked hard and took few vacations. But as a young father, Edward faithfully observed

Maundy Thursday (two days before Easter) by loading a keg of beer on the wagon and heading

out with his friends to go fishing, quite a distance from home. Edward apparently gave each son a generous $1000 when they left home, and perhaps

because of father-son clashes, they seemed to leave home as soon as they turned 21. Uncle Eddie

(Edward Ashorn Jr.), a little short fellow, went off to Bleiberville and never saw his father again,

returning only for his funeral. Edward's daughters stayed until they were married, but they

married young. Though Otto ran off too, to his uncle Willie and Emma Findeisen, he later

became his father's neighbor and had no animosity toward him.

Several of Edward's children lived on adjacent farms, since later in life, Edward divided up

his land among his sons in hundred-acre portions, like his father Christoph.

To visit Edward's farm today, take Schunka Road to the right off Hwy 109 after the New

Ulm cemetery, about two miles. The lane to the right goes to Edward's home. Originally the

farms were divided along the borders of fields, like a jigsaw puzzle, since they were informally

transferred from father to child. They were fenced and surveyed only when the owners died.

At

the end of his life Edward was diagnosed with stomach cancer. He lay in bed for some time in what the New Ulm Enterprise described as "intolerable pain"

that "left him entirely helpless." He died at 4 a.m. on April 25, 1934 in a Bellville hospital. The

Jugend Verein (Lutheran youth group) "sang very impressive hymns" at the afternoon funeral, which was conducted at Edward's home by Rev. H.C. Poehlmann, and sang at the gravesite in New Ulm's old town cemetery.

Edward's wife Rosalia Chaloupka (29) was born in Cermna, the same

Czech/Moravian town that Franziska Marek came from. Edward and Rosalia's home near New Ulm consisted of several buildings. His sons slept in a

large two-bedroom house outside the main house, where Edward stored his feed after his boys

were grown. The smokehouse was next to it. The original house had a good kitchen stove. A

pantry was attached to the house to store what they had canned, plus other staples. The house had

a long porch and a bedroom. At least in their later years, Edward and Rosalia slept in separate

beds. Adjoining the bedroom was the "güd stübe" (the good room), used as a parlor

or living room. The bedroom where the girls slept was called "Little Ettie's room" after all her older

sisters were gone. One well was right by the house, with a rope to draw water, and a second well

elsewhere. Rosalia liked to work in her gardens. One was behind the smokehouse, the other was

on the side of the house. She would raise different crops in the different gardens, depending on

what grew best where. Rosalia had guinea hens in a couple of places.

Rosalia always spoke German with her family, not English. She wanted to teach them Czech,

but Edward didn't speak it so he didn't want his children to learn it. But she would teach them a

little when he wasn't around. Though they didn't use it at home, her children could "mix in a few

words." Whenever Edward and his wife Rosalia got any mail, which was only every week or so,

their small grandson Riley would ride his white jenny up to the mailboxes to get it for them.

Later, when he got a Shetland pony, Rosalia said, "Wo hast du krache?" Riley was offended

because in German, "krache" means a broken-down skinny horse. Then his father explained that

the Czech word "krache" refers to any horse, and Rosalia used it even for the beautiful ones she

and her daughter Edith "Ettie" Schunka drove to town, riding in a buggy with the top down. One of Edward's two good horses

was named Prince. Riley doesn't remember seeing his grandfather drive, only his grandmother.

When Rosalia was old, she tended to wander from home across the fields. For a while she

lived with her daughter Ettie

Some of the Ashorns called Rosalie the "Platt Deutsch" because she spoke Low German, which as

Gloria Garrett demonstrates is more breathy, sibilant and low than the High German spoken by

the rest of her family. Her husband Edward Ashorn learned to talk like her if he wanted -- they

called him the "Platt Deutsch" too! Her daughter Rosa Buechmann and her family took over their farm.

Rosalie Hejl (59), the mother of Rosalia Chaloupka, was the daughter of

Josef Hejl (118), a farmer and gardener in Cermna, (now part of the Czech

Republic), and Johana Hausler (Hajsler) (119). Edmund Ashorn (14) was the husband of Emma

Findeisen and son of Edward Ashorn. His family says

he was always a cheerful man. Though he had a temper and might curse at the cows and mules, he was never harsh with his five children. His

daughter Gloria Ashorn Garrett says when he spoke firmly, "I thought I better behave," but he never whipped her. His former tenant farmer Ernest Platte also testifies to Edmund's good humor. On the other hand, Eloise McGinnis remembers her

grandpa in the 1940s as tall, straight and stern, saying "Eat that food. Don't you know I worked hard to raise

that food so you can eat it? Eat up and be grateful to the Lord Almighty." They did not attend church every Sunday, but nevertheless the children were taught not to

lean on their own understanding. At Christmas they would sing some of the old German songs.

Gloria remembers to her delight being given a corncob doll, and her father dressing up with a

Santa Claus mask, testing the children to see if they had learned their prayers. (Grandma

Franzeska made sure they had). In his bedtime prayers, Edmund would confess to God his sins of the day, including losing his temper.

Edmund was a very hard worker. After the cotton harvest, perhaps 200 pounds might be left

on the plants. Edmund wouldn't leave a boll. One year he had some of his nephews working

barefoot at Christmastime until all the remaining cotton was gathered.

Edmund never had a tractor, though he bought a Model A (which is still stored in the buggy

house at his farm). Like E.M. McGinnis, he commanded "Whoa" to

try to stop his first car. Sharecroppers lived in the little rent house and farmed part of land, giving

Edmund one-fourth of the harvest (E.M. McGinnis took half from his tenant farmers). He

continued to farm with mules into the 1960's. When he was 77, he fell off the hay wagon and

died in the hospital several weeks later.

Emma Findeisen (15) would rather be working in the fields alongside her

husband Edmund Ashorn than sewing or cooking indoors. Gloria remembers her childhood as "wonderful, peaceful, quiet days." The family raised

peanuts, cotton, corn, kohlrabi, cabbage, carrots, tomatoes, radishes, black-eyed peas, butter

beans, lima beans, pinto beans, sweet cane, and watermelons. Wild grapes grew along the fence

and climbed all over it.

The family had cows, mules, chickens, horses and other animals. A neighbor's horse-powered

press turned their sorghum cane into light-brown syrup after the children had carefully removed

all the leaves, wiped every stalk with a cloth and stacked them parallel on a tarpaulin on the

wagon. Her granddaughters remember her moist molasses cookies, always kept covered. Emma's family also

made their own soap with lye, grease and water. The clear grease was kept in

little fruit canning jars on the shelf. They would use the soap to clean everything in their

household except their skin. It was pretty strong. Her granddaughter Frances says her bedroom

on the farm smelled like Vicks ointment. When her children got sick, that's what Emma rubbed them

with.

Emma was much shorter than her descendants, who include Gloria

Ashorn Garrett (after whom Ariana Evangeline Loree is named) and Eloise Ann Garrett. She

would look at her great-grandsons Mike and Mark McGinnis and say, "Such big boys!" laughing

somewhat toothlessly. In her later years, she lived with her daughter Gloria's family in St. Louis,

where she constantly read her German Bible.

Carl Christoph Findeisen, Sr. (60) was born Feb. 12, 1799 in Lengefeld in

the Erzebirge Mountains in Saxony (then part of Prussia), a poor region not far from the Czech

border: a land of farms, the medieval Castle Rauenstein and the half-timbered knight's manor in

nearby Wunchendorf.

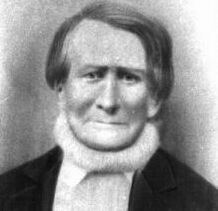

Carl Christoph Findeisen, Jr. (30) was a stout, quiet man with a goatee,

according to his granddaughter Gloria Ashorn Garrett. He came to

Texas from Lengefeld, Saxony at age 22 with the rest of his family and applied for U.S.

citizenship on April 26, 1858. After the Civil War, he farmed at Kirkendahl, near New Ulm, until

they moved in with Edmund and Emma Ashorn. He died November 16, 1914 not long after they

moved. Willie Findeisen took over the farm, and later moved to Sealy. His granddaughter Gloria

Ashorn Garrett, who was three years old when he died, remembers him as a very affectionate

man who called her "meine kleine Kindchen, meine kleine Elva" (my dear little child, my little

Elva) or "my loving bundle," as he bounced her on his knee.

Serving as an Confederate soldier along with his brother August in Waul's Legion Company

D, Carl Christoph was captured at the battle of Vicksburg, MS. One of the last two remaining

Confederate strongholds on the Mississippi River, Vicksburg fell to General Ulysses S. Grant on

July 4, 1863 after a six-week siege. Over 30,000 Confederate prisoners were captured and

immediately paroled back to their homes. But Carl remained a Union prisoner of war for eighteen

months before finally accepting parole just before the end of the war.

Franzeska Marek (31), Gloria Garrett's grandmother, was born in 1846 in

what is now Cermna, Czech Republic. She called it Rothwasser, Bohemia (then part of the

Austro-Hungarian Empire), or Czernowa Woda. Franzeska lived to be 95 years old, spending 25 years as a widow. She was very short and

stout, speaking German with no Czech accent. Sometimes she would take the train with her granddaughter Gloria Ashorn Garrett to visit her brother or her daughter Ella in

Temple TX. Every month, on a Saturday, she

would go out to the Wesley store to pick up

her Confederate widow's pension at the post office there. And she would buy herself a glass of beer.

"Zehr gut!" she told her granddaughter Gloria. But the girl didn't want to taste it.

For almost 30 years, Franzeska lived with her daughter Emma Findeisen Ashorn's family.

While Emma labored outside with her husband Edmund, Franzeska cared for her grandchildren,

fixed school lunches and cooked meals. She could make tasty soup out of scraps and never used

recipes. She would can pears, peaches and tomato puree for meat loaf. She was very neat and

clean. Franzeska was devout but open-minded. She used to say, "There is some good in every

church." Lillian Ashorn Wilhelm remembers how as a small child she could hardly wait to eat

Franzeska's savory homemade bread."

Next... Chapter

16: Elva Meets Alpheus

Narratives are taken from Pathway: A Family History, and may be freely distributed for non-commercial purposes.  When he was out of school and old

enough to take care of himself, he learned the tanner's trade. He came to Galveston, Texas on the

bark "Solon" from Bremen, Germany, on November 30, 1850, at the age of 26. Moving to

Frelsburg in Colorado County, he helped build the first Williard-Fehrenkamp Schueltegin.

When he was out of school and old

enough to take care of himself, he learned the tanner's trade. He came to Galveston, Texas on the

bark "Solon" from Bremen, Germany, on November 30, 1850, at the age of 26. Moving to

Frelsburg in Colorado County, he helped build the first Williard-Fehrenkamp Schueltegin. ![]() In the

fall of 1852, Christoph and William Meir bought 178 acres from Martha Pettus, the owner of the

S.O. Pettus League, through her agent Ellison York. Later Christoph bought out Meir. At his

property two miles north of New Ulm, Christoph built a tannery on the bends of Sandy Creek,

which became a lucrative business employing several men. The old vats were still plainly visible

in 1950, after 90 years. During the Civil War, Christoph served as a teamster, hauling

Confederate freight to and from Mexico on dangerous three-month trips, a vital link in the Texas

economy since trade with the North was impossible.

In the

fall of 1852, Christoph and William Meir bought 178 acres from Martha Pettus, the owner of the

S.O. Pettus League, through her agent Ellison York. Later Christoph bought out Meir. At his

property two miles north of New Ulm, Christoph built a tannery on the bends of Sandy Creek,

which became a lucrative business employing several men. The old vats were still plainly visible

in 1950, after 90 years. During the Civil War, Christoph served as a teamster, hauling

Confederate freight to and from Mexico on dangerous three-month trips, a vital link in the Texas

economy since trade with the North was impossible.

The marriage was performed by Rev. Johann Kilian,

Lutheran minister at Live Oak Hill in Colorado County. They built a log cabin on their part of the

land and settled down to farming and tanning. Christoph bought land in Austin County on Jan.

20, 1853, June 4, 1860, May 25, 1861, Jan. 2, 1873, Oct. 5, 1889 and Oct 9, 1899. By 1860, their

estate totaled $3000 in real estate and $200 in personal property. Christoph died in 1901 at 76

years, 9 months, 25 days and with his wife Carolina, is buried in the New Ulm Cemetery. She

died in 1899 at 66 years, 8 months, 3 days. At his death, his estate was valued at $10,000. He did

not learn English.

Today, Christoph's home, off Hwy 109 near the New Ulm Cemetery,

has been

completely restored by the Apache Foundation.

The marriage was performed by Rev. Johann Kilian,

Lutheran minister at Live Oak Hill in Colorado County. They built a log cabin on their part of the

land and settled down to farming and tanning. Christoph bought land in Austin County on Jan.

20, 1853, June 4, 1860, May 25, 1861, Jan. 2, 1873, Oct. 5, 1889 and Oct 9, 1899. By 1860, their

estate totaled $3000 in real estate and $200 in personal property. Christoph died in 1901 at 76

years, 9 months, 25 days and with his wife Carolina, is buried in the New Ulm Cemetery. She

died in 1899 at 66 years, 8 months, 3 days. At his death, his estate was valued at $10,000. He did

not learn English.

Today, Christoph's home, off Hwy 109 near the New Ulm Cemetery,

has been

completely restored by the Apache Foundation.

He was the father of Edmund Ashorn who married Emma

Findeisen.

He was the father of Edmund Ashorn who married Emma

Findeisen.

![]() In later years, he like to walk

around his farm with his hands behind his back, surveying his domain. In those days the

unfenced woods of the various farmers stretched from New Ulm to Bernardo.

In later years, he like to walk

around his farm with his hands behind his back, surveying his domain. In those days the

unfenced woods of the various farmers stretched from New Ulm to Bernardo.

Edward charged Otto

$60 an acre (a high price in those days). His $1000 gift provided the down payment and he

loaned Otto the rest at 6% interest. Otto's land was in a valley next to Edward's own remaining

farm. Inschrich lived on an adjacent hill, and Edward's daughter Edith "Kleine Ettie" Schunka

and her husband Joe lived on another neighboring hill. On a hill in another direction lived W.C.

Ashorn, Edward's youngest brother, on their father's original homestead (shown here after restoration by the Apache Foundation).

Edward charged Otto

$60 an acre (a high price in those days). His $1000 gift provided the down payment and he

loaned Otto the rest at 6% interest. Otto's land was in a valley next to Edward's own remaining

farm. Inschrich lived on an adjacent hill, and Edward's daughter Edith "Kleine Ettie" Schunka

and her husband Joe lived on another neighboring hill. On a hill in another direction lived W.C.

Ashorn, Edward's youngest brother, on their father's original homestead (shown here after restoration by the Apache Foundation).

In 1871,

her family settled in the Wesley area, near Bleiberville and Schoenau. She married Edward Ashorn on November

11, 1891 at Frelsberg, at a wedding conducted by Rev. Fritz Gerstmann. She was a hard worker,

tall and very slender, "as if the wind would blow her away," says Gloria Garrett. Compared to her

husband, she was very meek. Her parents attended the Unity of the Brethren Church in Industry. Rosalia

read her Bible every day, though her grandson Riley didn't see her in church much. He doesn't ever remember

seeing her husband Edward there. In fact, he didn't see his grandparents together much in public.

Riley thinks someone brought them groceries because he wasn't aware of them shopping.

In 1871,

her family settled in the Wesley area, near Bleiberville and Schoenau. She married Edward Ashorn on November

11, 1891 at Frelsberg, at a wedding conducted by Rev. Fritz Gerstmann. She was a hard worker,

tall and very slender, "as if the wind would blow her away," says Gloria Garrett. Compared to her

husband, she was very meek. Her parents attended the Unity of the Brethren Church in Industry. Rosalia

read her Bible every day, though her grandson Riley didn't see her in church much. He doesn't ever remember

seeing her husband Edward there. In fact, he didn't see his grandparents together much in public.

Riley thinks someone brought them groceries because he wasn't aware of them shopping.

![]() then went to her daughter Ella Henneke's home about

October, 1942 in the community of Bernardo, where Albert Henneke had a store. According to the death

certificate, which Albert signed, Rosalia died at 4:30 p.m. on February 7, 1946 after four or five days of

pneumonia. Her body was laid out at home before the funeral in New Ulm two days later, a cold winter day. Frnka

Funeral Home made the arrangements, and grandson Herbert Ashorn was one of the pallbearers. Rosalia left behind forty-two grandchildren and thirty great-grandchildren.

then went to her daughter Ella Henneke's home about

October, 1942 in the community of Bernardo, where Albert Henneke had a store. According to the death

certificate, which Albert signed, Rosalia died at 4:30 p.m. on February 7, 1946 after four or five days of

pneumonia. Her body was laid out at home before the funeral in New Ulm two days later, a cold winter day. Frnka

Funeral Home made the arrangements, and grandson Herbert Ashorn was one of the pallbearers. Rosalia left behind forty-two grandchildren and thirty great-grandchildren.

The family had intermarried with the Mareks, Silars and Duseks since the 17th

century or earlier, and they were fond of naming children after aunts and uncles, so the same

names appear every generation. Rosalie's parents were wed in 1825, and

Rosalie married

Vincenc (Chenek) Chaloupka (58) in the old country in 1850. By 1871, all of

Rosalie's siblings except one, plus her mother, had emigrated to Texas. Some of the Hejls were

put in heavy debt to their sponsors, but eventually owned farms of their own. Rosalie's oldest

brother Josef was one of the chief organizers of the Industry Brethren Church, part of a 19th

century Texas restoration of the long-suppressed Hussite Protestant movement dating back to

15th century Bohemia. The Brethren cemeteries of Texas contain the graves of Chaloupkas (her

husband's family), Hejls (her family), and Ficks (her daughter-in-law's family), as well as

Mareks. According to Hugo Findeisen, Rosalie had the same eye problems (macular

degeneration) shared by his cousin Gloria Garrett and himself.

The family had intermarried with the Mareks, Silars and Duseks since the 17th

century or earlier, and they were fond of naming children after aunts and uncles, so the same

names appear every generation. Rosalie's parents were wed in 1825, and

Rosalie married

Vincenc (Chenek) Chaloupka (58) in the old country in 1850. By 1871, all of

Rosalie's siblings except one, plus her mother, had emigrated to Texas. Some of the Hejls were

put in heavy debt to their sponsors, but eventually owned farms of their own. Rosalie's oldest

brother Josef was one of the chief organizers of the Industry Brethren Church, part of a 19th

century Texas restoration of the long-suppressed Hussite Protestant movement dating back to

15th century Bohemia. The Brethren cemeteries of Texas contain the graves of Chaloupkas (her

husband's family), Hejls (her family), and Ficks (her daughter-in-law's family), as well as

Mareks. According to Hugo Findeisen, Rosalie had the same eye problems (macular

degeneration) shared by his cousin Gloria Garrett and himself.

He made sure his grandchildren had straw hats to wear when they worked in the

cotton fields for him each summer. Though his children might have to walk two hours to school over

muddy, black lanes, he might pick them up after school in the wagon if it started raining.

Edmund liked eggs and sausage for breakfast, if he could get it, or fat slabs of German-style

bacon. For lunch he liked vegetables: tomatoes, lettuce, turnips. In the winter the family ate a lot

of sweet potatoes. The Ashorn family didn't have a lot of books, even though all their children

except Herbert were educated past high school. They did have dictionaries, however, in German,

French and Spanish.

He made sure his grandchildren had straw hats to wear when they worked in the

cotton fields for him each summer. Though his children might have to walk two hours to school over

muddy, black lanes, he might pick them up after school in the wagon if it started raining.

Edmund liked eggs and sausage for breakfast, if he could get it, or fat slabs of German-style

bacon. For lunch he liked vegetables: tomatoes, lettuce, turnips. In the winter the family ate a lot

of sweet potatoes. The Ashorn family didn't have a lot of books, even though all their children

except Herbert were educated past high school. They did have dictionaries, however, in German,

French and Spanish.

![]() It was cold! When the crops failed one year, Edmund

had to borrow money, even for shoes. Because he couldn't pay his debts, he lost part of the land

to Billy Tillemann, the man who sold it to him. "Let it go, let it go!" Edmund said. But the next

year, when he harvested a good cotton crop, he was able to buy it back. His eldest daughter Gloria

enjoyed going with him to Brenham, when he would hitch up the wagon and two mules to sell

cotton seed or corn. They would often buy cheese and crackers at Schmitz Market to eat on the

way home. Watermelon was the favorite treat for children and later, grandchildren, working in

the cotton fields on a summer day. Sometimes Lillian, his youngest daughter, would crack a watermelon with her

hands to feed to her nieces and nephews. Edmund's granddaughter Evelyn says, "You

never could get enough watermelon."

It was cold! When the crops failed one year, Edmund

had to borrow money, even for shoes. Because he couldn't pay his debts, he lost part of the land

to Billy Tillemann, the man who sold it to him. "Let it go, let it go!" Edmund said. But the next

year, when he harvested a good cotton crop, he was able to buy it back. His eldest daughter Gloria

enjoyed going with him to Brenham, when he would hitch up the wagon and two mules to sell

cotton seed or corn. They would often buy cheese and crackers at Schmitz Market to eat on the

way home. Watermelon was the favorite treat for children and later, grandchildren, working in

the cotton fields on a summer day. Sometimes Lillian, his youngest daughter, would crack a watermelon with her

hands to feed to her nieces and nephews. Edmund's granddaughter Evelyn says, "You

never could get enough watermelon."

He

was more stubborn than Emma was. She was more patient and affectionate than Edmund was.

When her children got out of line, she hardly did more than slap their hand. The couple farmed

near Wesley, south of Brenham, TX. At first they lived in the old farmhouse, but later they built a

new one with a fireplace. Later Emma's son Honey (Edmund Jr.) persuaded them to build the

home which Lillian Wilhelm owns today. They didn't have electricity until the 1940's. She

remained close to her twin sister Ella.

He

was more stubborn than Emma was. She was more patient and affectionate than Edmund was.

When her children got out of line, she hardly did more than slap their hand. The couple farmed

near Wesley, south of Brenham, TX. At first they lived in the old farmhouse, but later they built a

new one with a fireplace. Later Emma's son Honey (Edmund Jr.) persuaded them to build the

home which Lillian Wilhelm owns today. They didn't have electricity until the 1940's. She

remained close to her twin sister Ella.

Meat came through a "butcher club" in the days before refrigeration. Each week, on a Tuesday or

Friday, a different family would furnish a grown calf for slaughter and each family in the club

would get a share. A traveling butcher would kill, bleed, skin the large calf, then cut it into

sections once it was cool. After dressing the carcass, the traveling butcher would weigh the calf.

The dressed weight of their calf determined the family's yearly meat allotment. If they needed

more, they would have to pay extra. Large families might provide two calves a year in order to

have enough. Each portion of meat went into a clean flour sack and the family would cut their

roasts and steaks out of that. They would have to cook it within a day so it wouldn't spoil, and

they would eat it all week long. For his part, the butcher wouldn't have to provide his own calf, or

he would keep the hides, or else he would be paid $10 a year. Even the butcher in town might run

his own club. Families would request certain cuts and the butcher might smile and say, "That calf

didn't have all steak. You're going to have to take something else." Most of the meat came in the

form of roast. Families would store it in a pie safe with punched tin instead of glass.

Meat came through a "butcher club" in the days before refrigeration. Each week, on a Tuesday or

Friday, a different family would furnish a grown calf for slaughter and each family in the club

would get a share. A traveling butcher would kill, bleed, skin the large calf, then cut it into

sections once it was cool. After dressing the carcass, the traveling butcher would weigh the calf.

The dressed weight of their calf determined the family's yearly meat allotment. If they needed

more, they would have to pay extra. Large families might provide two calves a year in order to

have enough. Each portion of meat went into a clean flour sack and the family would cut their

roasts and steaks out of that. They would have to cook it within a day so it wouldn't spoil, and

they would eat it all week long. For his part, the butcher wouldn't have to provide his own calf, or

he would keep the hides, or else he would be paid $10 a year. Even the butcher in town might run

his own club. Families would request certain cuts and the butcher might smile and say, "That calf

didn't have all steak. You're going to have to take something else." Most of the meat came in the

form of roast. Families would store it in a pie safe with punched tin instead of glass.

![]() He was christened and married at the Evangelical

Lutheran Holy Cross

Church there, with its tall narrow steeple and stout walls, just as all his family had been since

1624 or earlier. Carl Christoph's father was a Buerger(city councilman) as well as a Gutsherr(squire) and a Huefner(shoemaker). The

Findeisens were known as horse breeders, farmers, blacksmiths and furniture makers. They

married into the Goebel family, who made violins. In 1854 Carl Christoph,

his wife

Johanna Dorothea Hetzel (61) and their nine children left Bremerhaven,

Germany on the ship "Lucy" and arrived at Galveston, TX on Nov. 7, 1854. The family settled in

Cat Spring, Austin County, TX. He died in the cholera epidemic of 1867. His grave and that of

two others was recently rediscovered on a private farm by leaders of the annual Findeisen

reunion, who erected a stone monument on the site.

He was christened and married at the Evangelical

Lutheran Holy Cross

Church there, with its tall narrow steeple and stout walls, just as all his family had been since

1624 or earlier. Carl Christoph's father was a Buerger(city councilman) as well as a Gutsherr(squire) and a Huefner(shoemaker). The

Findeisens were known as horse breeders, farmers, blacksmiths and furniture makers. They

married into the Goebel family, who made violins. In 1854 Carl Christoph,

his wife

Johanna Dorothea Hetzel (61) and their nine children left Bremerhaven,

Germany on the ship "Lucy" and arrived at Galveston, TX on Nov. 7, 1854. The family settled in

Cat Spring, Austin County, TX. He died in the cholera epidemic of 1867. His grave and that of

two others was recently rediscovered on a private farm by leaders of the annual Findeisen

reunion, who erected a stone monument on the site.

The name means

"red water" in all languages. Her father was a buergermeister or town leader, and as a tailor made fine suits. Her mother died

from sickness she caught caring for someone after she was warned that her kindness might cost

her life. Franzeska often talked about the beautiful rolling hills of home. She came to Texas alone

at age 23 on the ship "Bremen" on May 10, 1871, a six-week voyage. Her brother Joseph came

first, perhaps sending money for her passage, and worked for many years with a funeral

home near Temple.

The name means

"red water" in all languages. Her father was a buergermeister or town leader, and as a tailor made fine suits. Her mother died

from sickness she caught caring for someone after she was warned that her kindness might cost

her life. Franzeska often talked about the beautiful rolling hills of home. She came to Texas alone

at age 23 on the ship "Bremen" on May 10, 1871, a six-week voyage. Her brother Joseph came

first, perhaps sending money for her passage, and worked for many years with a funeral

home near Temple.

When faced with

stained clothes Edmund had worn on the haymower, she would instruct young Gloria, "Scrub this

real good," but if Gloria didn't do it with enough speed or energy, Franzeska would take it right

back and "scrub and scrub" in a flurry of hands with a bar of homemade soap. Only for tough

stains did she use a washboard or soak the clothes.

When faced with

stained clothes Edmund had worn on the haymower, she would instruct young Gloria, "Scrub this

real good," but if Gloria didn't do it with enough speed or energy, Franzeska would take it right

back and "scrub and scrub" in a flurry of hands with a bar of homemade soap. Only for tough

stains did she use a washboard or soak the clothes.

![]() We

must thank God first," her grandmother reminded her

in German (She spoke no English).When she put the children to bed, she expected them to pray,

"or she'd pray for them." Gloria Ashorn Garrett would read to her out of the German Bible,

though Franzeska owned a Czech Bible. When sometimes Franzeska would try to talk to Gloria

Ashorn Garrett in Czech, she would reply, "Grossmutter, ich kann nicht verstein!" (Grandmother,

I cannot understand!). But Gloria can still speak a few phrases in Czech.

We

must thank God first," her grandmother reminded her

in German (She spoke no English).When she put the children to bed, she expected them to pray,

"or she'd pray for them." Gloria Ashorn Garrett would read to her out of the German Bible,

though Franzeska owned a Czech Bible. When sometimes Franzeska would try to talk to Gloria

Ashorn Garrett in Czech, she would reply, "Grossmutter, ich kann nicht verstein!" (Grandmother,

I cannot understand!). But Gloria can still speak a few phrases in Czech.

MAPS

- Back to Top -

New Ulm & Frelsburg, TX

Wesley, TX

Welcome & Bleiberville, TX

;

;

© 1996-2004, Michael McGinnis, Bryan, TX

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()